The Oracle’s Room

“The Oracle’s Room: Thirteen Faces of Fate constitutes a formally cohesive and conceptually ambitious body of work that engages the viewer in an intimate dialogue with the visual languages of archetype, ambiguity, and interiority. This series of thirteen paintings, each depicting a solitary female figure suspended in a liminal space of psychic intensity, forms a ritualized cycle — or perhaps a disrupted cycle — of reflection on fate, perception, and the suspended moment of becoming.

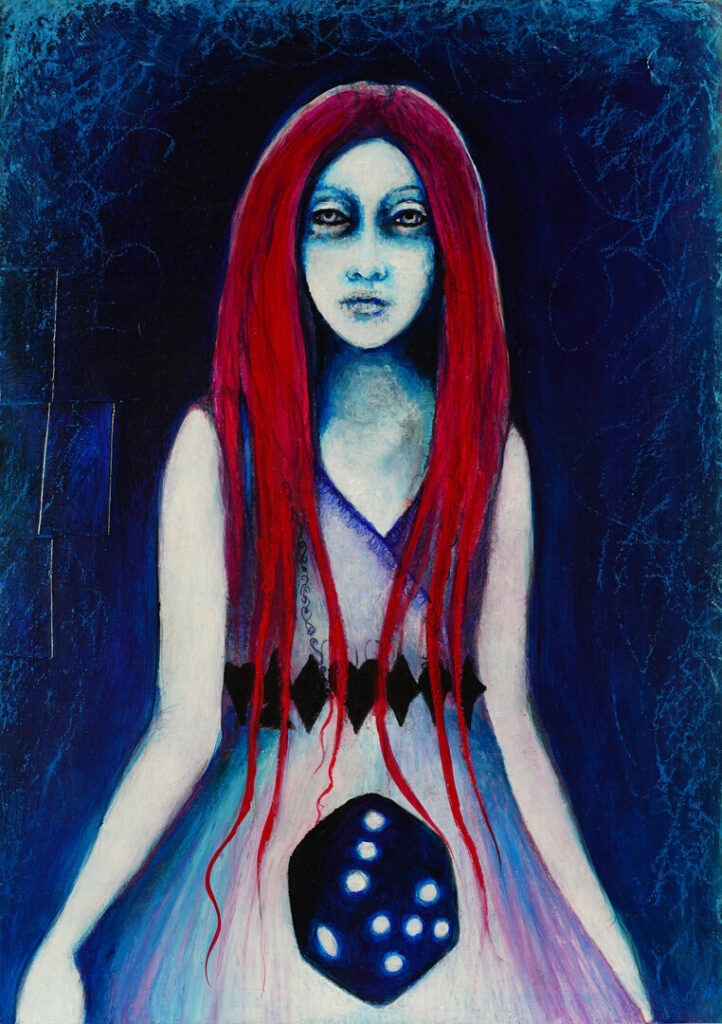

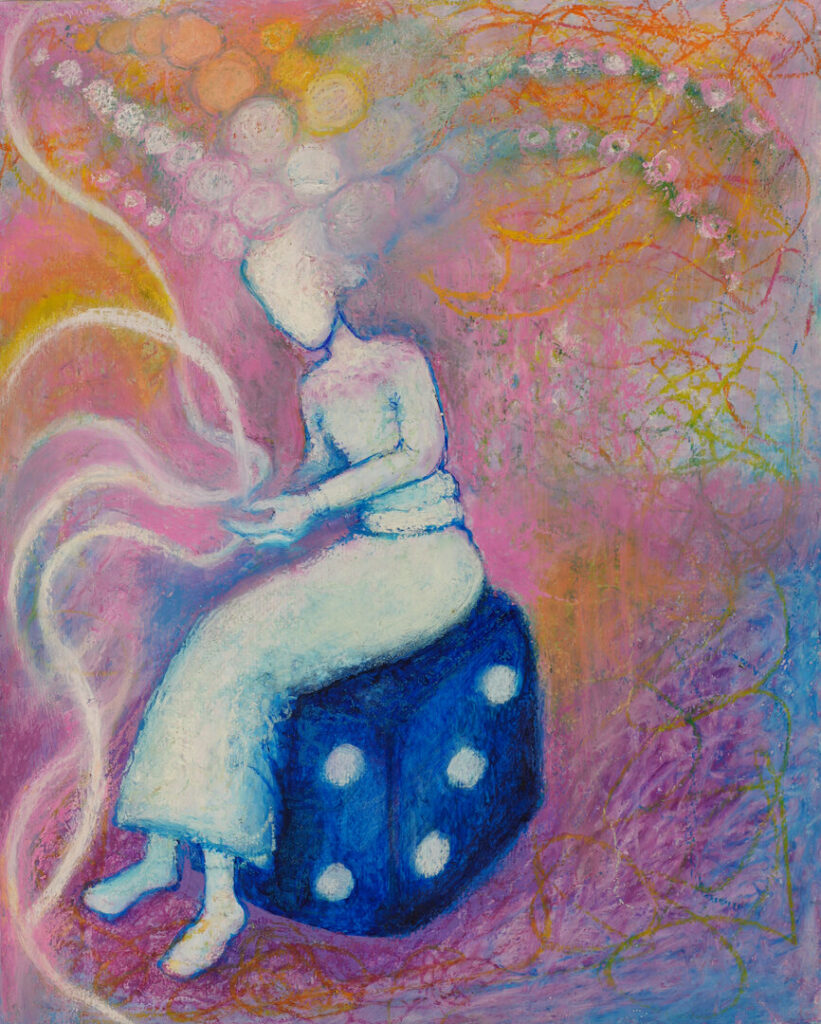

Rendered in a palette that oscillates between electric ultramarine, spectral violet, and the intense reds of hair, thread, wound, or object, the paintings enact a mythopoetic visual grammar. While the influence of Surrealism and Symbolism is apparent — especially in the dreamlike staging and the corporeal transpositions of symbolic forms — these images resist narrative closure. The artist does not illustrate a myth; instead, she constructs a room of oracles who are simultaneously subjects and thresholds.

Each face of fate is emblematic, yet ultimately unknowable. The figures do not pose; they confront. They are not conduits for external prophecy but embodiments of internal constellations — psychic configurations where memory, desire, and chance entangle. Their stillness is not a retreat from agency but a transformation of it. For instance, the frequent presence of dice — often coded in Western iconography as symbols of randomness or divine will — is here internalized. The die appears in the lap, womb, or abdomen, suggesting that fate is not thrown outward but incubated.

The series displays a structural coherence in both compositional balance and chromatic orchestration. Almost all the figures are centrally framed, vertically elongated, and placed against spatially ambiguous backdrops. This compositional stability functions as a formal analog to the thematic stillness: a theater of inwardness. The backgrounds are suggestive of voids, constellations, or cognitive storms — dense with linework, texture, and ethereal illumination. These are not environments but psychic weathers, each tuned to the figure’s particular frequency.

The chromatic field is carefully restricted, generating a chromatic mood rather than narrative symbolism. The electric pinks, purples, and blues coalesce to evoke states of heightened perception. Red, used sparingly but precisely — in hair, hearts, dice, or strands — punctuates the cool palette like a rupture, a cipher of danger, desire, or bloodline. Light itself appears metaphysical rather than logical. The figures often seem lit from within or from an unknowable source — reinforcing their status as beings of vision rather than visioned.

An important motif across the series is the relationship between body and object: dice, hearts, trees, threads, spheres. These items are not props; they are extensions or organs of the self. In one painting, a heart-shaped wound opens in the figure’s chest; in another, the woman’s torso appears as a translucent veil around a glowing die. A tree blooms from a black field, its roots and branches laced with orbs of possibility. Elsewhere, strands of filament-like energy emanate from the fingers or scalp — visualizations of invisible forces. These transpositions suggest a metaphysics of embodiment: the self as a vessel of perception, a locus where symbol and sensation collapse.

The seriality of the thirteen paintings functions not only numerically but ritually. Thirteen, historically associated with lunar cycles and feminine rhythms, marks a liminal zone between order and rupture — a kind of esoteric completeness that defies the neatness of twelve. The Oracle’s Room, therefore, is not merely a metaphorical chamber but a conceptual architecture: a psychic cloister of indeterminate knowing, a secular shrine to the ambiguous, the withheld, the never-quite-said.

Viewed as a whole, The Oracle’s Room: Thirteen Faces of Fate is a sustained meditation on feminine archetypes outside of patriarchal legibility. The figures offer neither seduction nor salvation. They withhold interpretation even as they provoke it. Their gazes are not mirrors but thresholds. In the artist’s own words, they are “emotional architectures” — not illustrations of story, but sites of concentrated presence.

This body of work contributes to a lineage of contemporary symbolic figuration, aligning with artists who seek not to narrate identity but to stage perception. Its philosophical resonance is matched by its formal discipline, resulting in a suite of works that invites not decoding but durational looking — a mode of attention that is increasingly rare, and thus increasingly necessary.”